Welcome to Copywriting Night School. As mentioned, I am going to teach you to write your copy by working backwards — starting at the very end of your funnel, and working toward the beginning.

But before you can start writing, there is one thing you absolutely have to know first...

What are you selling?

Copywriting, you may have heard, is salesmanship in print. I’ll actually examine that definition rather critically in a later lesson, but it makes the point well enough: the aim of all your copy is ultimately to get your prospect to buy something.

But before we continue, let’s stop saying “your prospect.”

Let’s call your prospect “Sam.” Maybe it’s Samuel; maybe it’s Samantha; maybe both. Not only is this much easier than saying “your prospect” all the time, it also has the benefit of encouraging you to write personally — something I will talk about extensively quite soon.

Now, I assume you already know what you want to offer Sam. Three common options are:

A subscription (for total customer value over time, this is a great option).

A one-time product purchase.

A consultation, whether paid or free, that will lead to a project (this is common for freelancers selling a service like web design, lead-generation etc).

You might be offering something different, and that’s okay. I’m not going to tell you what you should be offering — I assume you’ve worked that out. Rather, I want you to think about how to offer it. This becomes very important when you’re writing your call to action in the next lesson.

How to make your offer

At the most basic level — obviously — you need to demonstrate value to Sam. The whole point of your offer is to give him something valuable.

But a fundamental problem people run into, even before they put words on the page, is a critical error I call the “value fallacy.”

Since the value fallacy is directly related to your offer, it’s the very first thing we need to talk about.

When you think about writing your offer, you naturally try to work out how to demonstrate its value. But how you think about value tends to diverge rather notably from how Sam thinks about it. You tend to focus narrowly on monetary cost; but there are actually three “value metrics” that Sam considers — of which money is usually the least important.

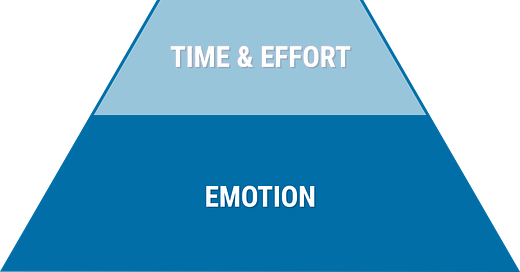

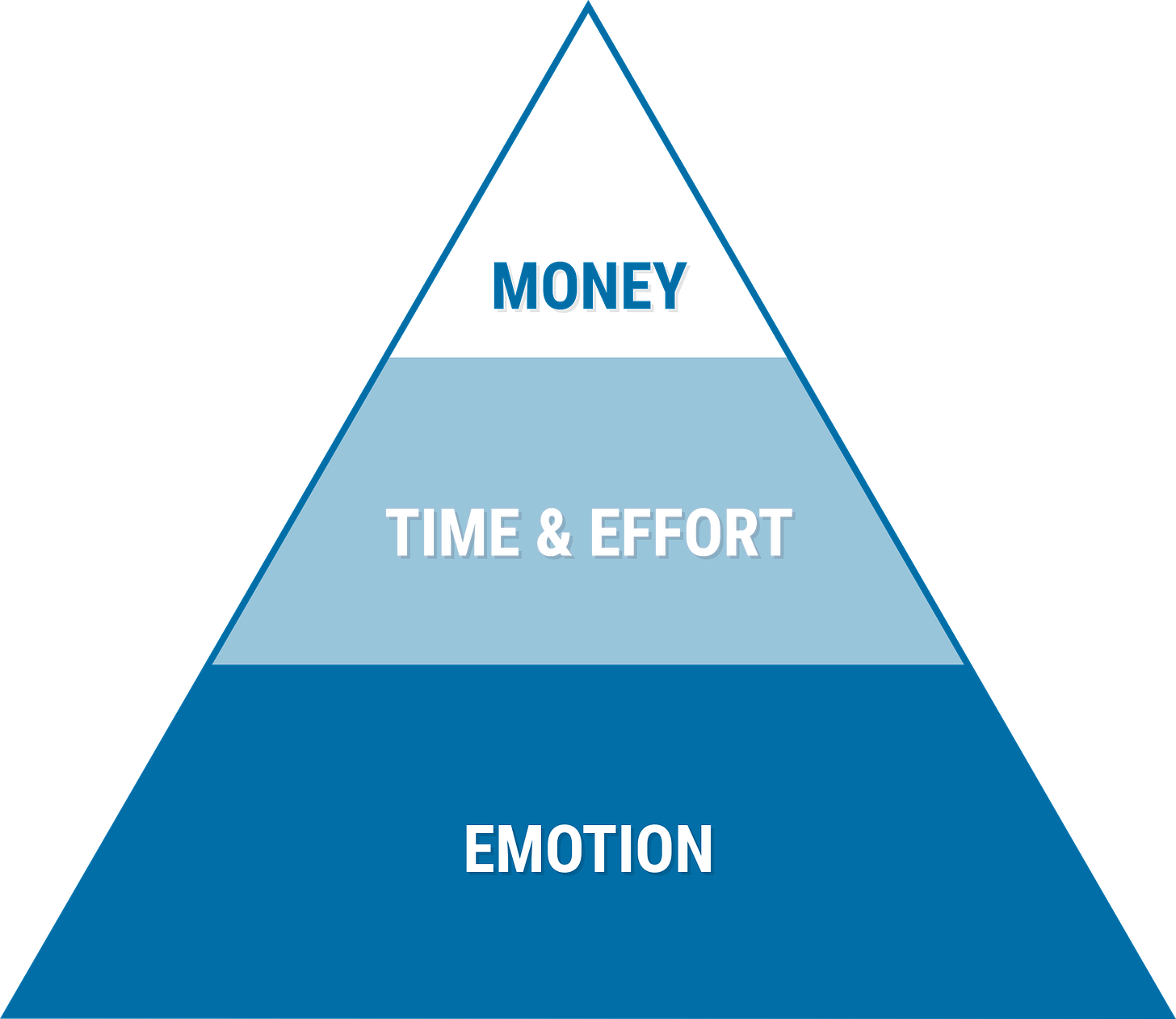

You can imagine a kind of food pyramid for value:

As you can see, emotion forms the foundation of the pyramid — and emotion cannot be measured in scientific units. This means no matter how much money you might show Sam that he can get or save by accepting your offer, if the emotional toll seems high then you’re SOL.

He is measuring the perceived cost in something more valuable than dough.

This is especially important if you’re offering a consultation or a quote. Sam knows he is going to have to interact with you...and you might pressure him to say yes when he doesn’t want to.

This causes anxiety.

Anxiety is the conversion-killer.

The important takeaway when approaching any copywriting project is to think of emotions first. If you can figure out Sam’s emotional drivers, and assign them the appropriate weight, the rest tends to follow quite naturally. But if you don’t figure out what he will regard as valuable early on, you tend to get blinkered, and a gap builds up between what he wants, and what you want to give him.

Bridging the gap

Ultimately, how much value Sam thinks you’re offering is all about perception. There is no objective metric of value — it is all perceived.

You want to find the way to present your offer that Sam will perceive as most valuable. You can bring about large shifts in his perception by making quite subtle changes to one or both of:

What you’re offering

How you’re offering it

This is called reframing.

Rory Sutherland, a very funny ex-advertising man, gives an example of reframing in a talk called Perspective is Everything:

If you have a spare 18 minutes and 25 seconds, watch the whole thing. But let me relate one example he uses, to give you a sense of what reframing is all about:

A train company in the UK called Eurostar spent £6 million on reducing the travel time between France and England by 40 minutes. The problem, as they saw it, was that people wanted to get across the channel more quickly. Or, put another way, customers wanted to spend as little time on the train as possible. So that’s the problem they set about to fix.

But what if, instead of accepting the way in which the problem had been framed, they had simply turned it on its head?

What if instead of asking how to reduce the amount of time customers had to spend on the train, they had asked how to increase customers’ desire to spend time on it? So instead of spending £6,000,000 on cutting the duration of a trip that was basically “dead time” to customers, imagine if they had fixed the problem of dead time itself by installing wifi access on the trains. This would have made the trip more enjoyable and productive for most passengers...and cost 1% of the original budget.

Or what if instead of spending £6 million, they had spent just £1 million and hired the world’s top male and female supermodels to hand out free liquor and snacks? There’d still be £5 million in change, and passengers would ask for the trains to be slowed down!

This latter option is obviously facetious (not to mention making certain ethical assumptions I am unlikely to agree with). But the facetiousness, at least, is part of the point: we prioritize “technical” solutions over psychological ones. Why does a psychological solution like this seem less than serious (assuming we could make it work long-term), when it would save the company millions of pounds, raise customer satisfaction, and bring in no doubt many more millions of pounds in extra custom within a year?

I want you, in your own business, to take psychological solutions seriously.

So that illustrates the general idea, but it isn’t terribly helpful given that you’re not selling seats on trains. So here is a more practical example, from my own business:

I used to sell a subscription newsletter called the Shirtsleeves Marketing Communiqué. It was quite broadly focused on improving your marketing. At least, that’s how I presented it.

In truth, I talked about conversion-rate optimization. The way I look at it, conversion-rate optimization just is marketing — the discipline of generating more leads and more sales.

About half-way through its 2-year run, I acted on a suspicion, and rebranded (reframed) the newsletter as the Attention-Thieves’ Communiqué, billing it as a monthly conversion optimization mailer. And I nearly doubled the price.

After making these two small changes, my subscription rate increased noticeably.

Four practical steps to effectively frame the value of your offer

Before we start writing tomorrow, here are some simple ideas for you to ruminate over:

1. Avoid goal dilution

As a seller, you are typically afraid of excluding any potential customer. But as a buyer, Sam assumes that if you focus narrowly on one thing, you will be better at it.

In the example above, my customers assumed that my newsletter would be better at teaching them to generate leads and sales if it was narrowly focused on CRO, as compared to when it was broadly focused on marketing. This despite the fact that it’s all the same thing to me.

It is better to focus your offer, than to make it broad. Be specific about who your ideal customer is, and what exactly he wants.

Assuming your ideal customer fits the profiles below, and realizing that you can develop funnels to sell other offers later, it is better to...

offer copywriting for freelancers than copywriting for anyone;

offer copywriting for the web than copywriting for any medium;

offer single-page web-design services than any and all web development;

offer cake-baking tips to complete newbies than general cake-decorating advice to anyone with an interest.

You get the idea. Adjust to your own offer as necessary.

2. Avoid being generic

The language you use determines how Sam thinks about your offer. George Orwell understood the power of language for shaping thinking, but I am not suggesting that you be Orwellian. Rather, you should be interesting. When Sam has seen something before, he switches off. Why would he bother investigating something he thinks he already knows? Conversely, unique terms signal to Sam that he is getting something unique.

Many freelancers offer “initial consultations”. That’s a very generic term, and it doesn’t help you stand out from the crowd. Why would Sam want your initial consult over someone else’s? Compare that to offering, say, a consult called “10 ideas to get 10 more clients in 10 minutes.” For my own part, I developed VAMS: Value Analysis & Messaging Strategy.

If you were a boutique web designer, you could say something like “hand-stitched code.” One of the simplest ways to reframe is to hit a thesaurus and find synonyms for what you’re offering — words that say the same thing, but carry unusual or desirable connotations.

3. Identify hidden costs

Don’t forget about the value fallacy here when you think of what a “cost” is. You want to put yourself in Sam’s shoes, and ask yourself what kinds of anxieties — even subconscious ones — he might have about your offering. Aside from the obvious monetary cost...

Is he likely to sense an emotional cost? Does he feel guilty about needing to buy? Or ashamed? Does he suspect he lacks some ability he needs to make use of your offering? Or is he afraid of feeling pressured, stupid, or disappointed?

Is he likely to think that the effort isn’t worth it? Will he perhaps assume he doesn’t have time? Or that it will be too hard compared to the reward?

You’ll see how these issues play out in lesson 4. For now, just think about these questions.

My very first, flagship product was called called Attention-Thievery 101. It was basically a bunch of PDF documents that taught you the major principles of conversion optimization. But it came with two major costs to Sam:

The effort of working through all the content in such an unappealing format. Reading multiple PDFs like that is hard work. You have to have the gumption to read all the way through the course — the content is all there in front of you at once, and you just have to read and read and read. I did my very best to make this easy and enjoyable, but let’s be honest — it’s a lousy format for learning. Even today, when reading digitally is much more comfortable because of tablets and high-quality screens, it just kinda sucks to have to wade through huge wads of text.

The emotional cost of having to either try to absorb everything very quickly, or remember to keep reading methodically over a period of days or weeks. No one really wants to have this kind of hassle. Everyone knows that they tend to forget things they’ve accidentally closed or moved to the background. And enthusiasm for new content tends to wane quickly even if you remember it. Who wants to buy something they suspect they won’t have the discipline to fully read and follow through on?

I reframed this product very successfully, and sold exactly the same content for three times the price, by turning it into a timed-release video course called Attention-Thievery Academy.

In other words, I changed the delivery format to overcome the costs to Sam, by reframing the product from a DIY manual to a guided education. I restructured the content to be extremely easy to digest. Each video was between 10 and 20 minutes because the human brain has a natural attention limit of 20 minutes — after that you need to shift gears. Customers only got three videos a week.

Same basic content. Completely different sense of its value.

Two practical ways to identify hidden costs

Ask customers for refund/cancellation reasons. If someone wants out, that’s a learning opportunity — there’s a good chance you failed to meet an expectation which represents a hidden cost. Something you did, or didn’t do, wasn’t right, and knowing what it was can help you better frame your offer. Never try to make people justify themselves here; you aren’t saying, “I’ll refund you if you can explain why I should!” Rather, you’re saying, “No problem, that’s all taken care of. You don’t have to answer this, but do you mind telling me why the offer didn’t meet your expectations? It might help me improve things for my other customers.”

Ask about challenges. You can do this automatically with email, as we’ll discuss in depth later on. Customers often love to tell you about their challenges. This gives you insight into what they’re struggling with, and the exact words they’re using to describe their problems. All great ammo for refining your offer to better fit Sam’s perceptions — or for creating a new offer. That’s how I originally created this training program.

4. Identify hidden rewards

This is simply the opposite of step 3. Just as there are hidden costs in any offer, there are usually rewards for Sam that you won’t immediately pick up on. Identifying these in advance will be useful for setting you on the right track when you craft things like headlines and benefit bullets.

What emotional reward might he get from your offering? Renewed confidence? Looking like a hero to others? The ability to sleep at night? Less stress, or a clearer understanding of something? Feeling good about his relationship with someone else (maybe if you’re selling gifts for example)? More time to have fun with his family or friends?

What time or effort-based rewards are there? Time with family (also an emotional reward)? Less stress? The ability to make something he didn’t think he could make?

You notice that there’s overlap between time-based and emotional rewards (and costs). That’s because ultimately everything comes down to emotion — even money. Time, money, effort...they are all just abstractions of emotional reward or cost.

Perceived value, price, and knowing your customer

Something to keep in mind that relates back to points 1 and 2: sometimes it is better to go after harder, higher-value customers than the low-hanging fruit. And sometimes it is better to do the opposite. It depends on how much work is involved for you, and how much money you can make from each.

It comes down to really knowing your ideal customer.

You might be able to reframe a low-priced offer into a higher-priced one that gets fewer sales, but more overall revenue. Often high-value customers are much better customers overall. I suggest this strategy in general. But sometimes the opposite is true: some offers make far more sales and far more overall revenue when they are priced low.

Changing your price, or presenting it differently, is a valid way to reframe.

You may have heard the oft-cited case study from the beginning of Cialdini’s Influence. A jeweler was having trouble selling some high-quality turquoise pieces — even though they were prominently displayed and priced very reasonably. She had even tried getting her staff to point the pieces out to shoppers, but they just didn’t seem interested.

In the end she figured she’d have to take a loss to get rid of them, so she wrote a note to one of her sales staff saying that everything in the turquoise display case should be priced “times ½.”

This was misinterpreted as an instruction to double the price. The pieces immediately sold out like hot cakes. (What exactly are hot cakes? Why would you want a hot cake? Why do they sell so well? These are questions to which I do not have the answers.)

The moral: price strongly affects perception. In many industries, the price of an item is essentially the only metric customers use to decide its quality.

It’s hard to know the effect price will have without testing. Sometimes reducing prices increases revenue too. For example, a split test by MarketingExperiments compared three price points with the following results:

Price Sales Revenue

-------------------------------

$10 156 $1,560.00

$12.50 94 $1,175.00

$14.95 74 $1,106.30What’s particularly informative about this case is that “charm prices” like $14.95 generally perform best — by an average of 24% if you believe William Poundstone. Yet here, the charm price performs worst.

“Changing” your price can also simply mean reframing it — usually by implicit comparison, aka price anchoring. Items in an auction with a low initial bid price will usually sell for more if they’re positioned next to very similar items with much higher initial bid prices.

This is why so many websites use 3-tiered pricing systems: the bottom tier can be a “dummy.” Few people want the cheapest deal; rather, they want the best deal. Having an option which is priced a little above the cheapest tier, but which offers a fair bit more, provides the kind of implicit price comparison Sam needs to see the middle tier as a great deal.

Once again, it comes down to how he perceives value.

You might be wondering when you’re going to get to write some copy. The answer is tomorrow. I know this talk of value and framing seems a little abstruse right now. But if we don’t deal with it very early on, you end up getting a nasty surprise later — and start to feel like you need to completely revise your offer. That would mean revising your call to action, which would mean revising your entire sales page and email sequence...and it’s just a nasty mess.

Forewarned is forearmed.

That said, there are some things you can do to prepare for tomorrow:

Homework

Draw the value pyramid. Like, physically get a pen and paper and diagram it. You want to make sure it’s cemented in your mind — and while we will go over it again, nothing beats physically taking notes.

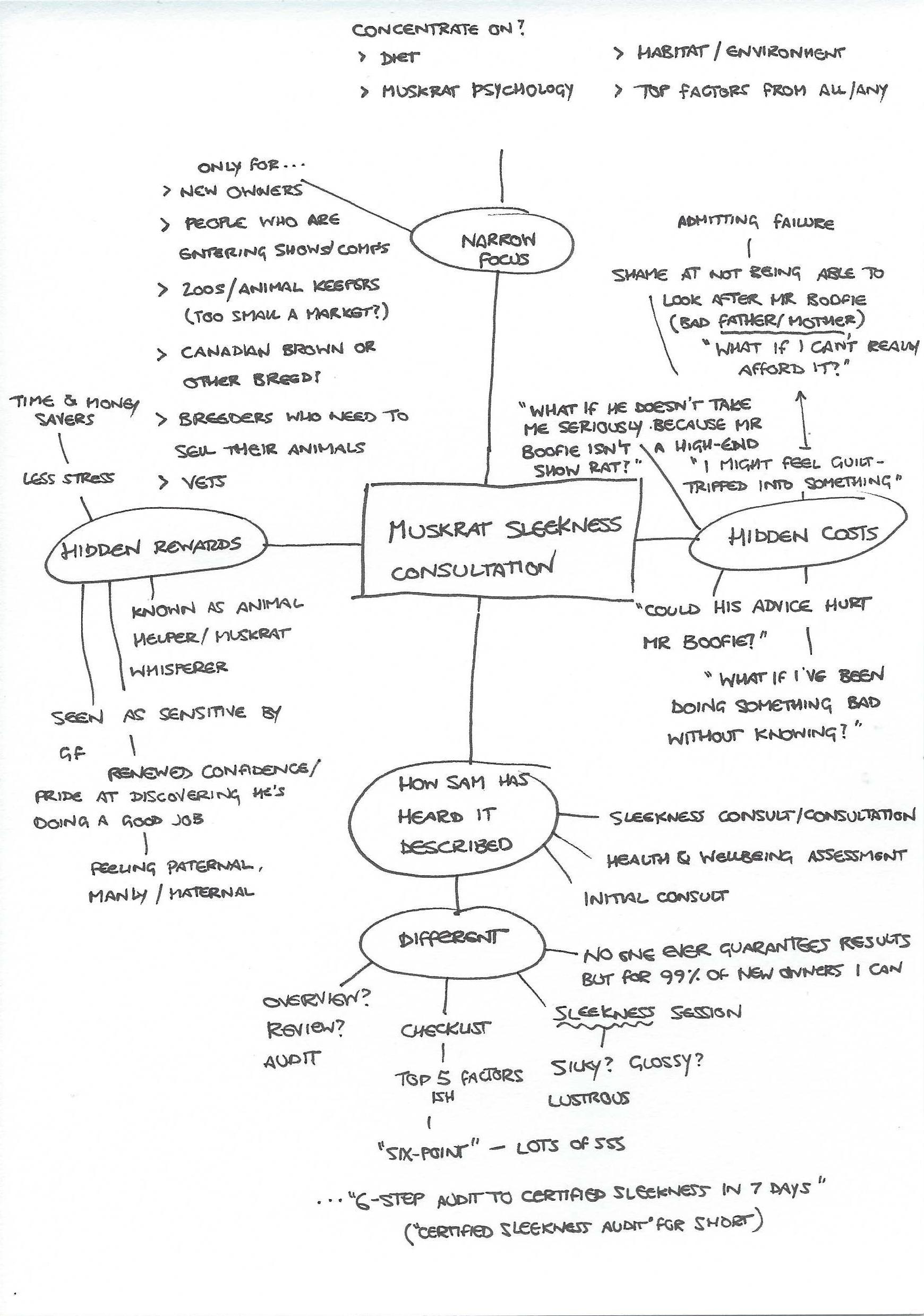

Relying on the value pyramid, write your offer in the middle of a piece of paper, and brainstorm:

Ways to narrow its focus and avoid goal dilution

How Sam has already heard it described, and how you can describe it differently

Hidden costs (emotional and time/effort-based)

Hidden rewards

Here’s an example I did myself: