So far we’ve focused on writing copy that, being further down the page, assumes that Sam is already interested and engaged.

But how do you get the momentum going in the first place, for that engagement or interest?

Obviously it has to start with your headline. That’s where Sam starts reading — and where he ends, if things don’t look promising. But as you know, trying to learn to write the hardest, most important copy first is a bad idea.

So this week, you’ll be learning another element which is only a hop, skip and a jump away from a headline, and teaches another of the 4C principles — namely contrast.

Contrast might sound like an obvious enough concept, but it cashes out in a number of surprising ways that you may not expect.

For example, it is the “active ingredient” in a broad range of copywriting techniques...

Making Sam laugh

Staking out a strong position on a controversial topic

Trying to persuade Sam not to buy

Attacking common enemies

Telling personal anecdotes and weird stories

Emphasizing a unique selling proposition

Blowing the whistle on shenanigans in your industry

Using fascinations (curiosity/interest bullets)

This week, we’ll be focusing on that last item — fascinations. How you write these differs depending on your offering. Physical products and online services, for instance, are not suited to piquing Sam’s curiosity, but rather raising his interest level. But whatever you sell, you can use contrast to write powerful bullets.

Before we get there, however, you need to understand contrast in general. And here’s why it is so important:

If you use clarity correctly, without contrast, it can actually reduce Sam’s interest in your offering.

How can that be?

Well it ain’t rocket surgery. Simply put, clarity helps Sam to grasp what you’re saying quickly and easily. The more quickly and easily he grasps it, the more quickly and easily he is likely to say, “Meh, I’ve heard this before — nothing to see here.”

And so the more quickly and easily he’s gonna ignore you and move on.

This is obviously more of a problem in some industries than others...but unless you’re in a magical, completely new market of rainbows and unicorns, there’s no escaping the fact that you have to differentiate yourself somehow. If you don’t isolate yourself in Sam’s mind in a meaningful way, then using the other parts of the 4C Cipher actually makes it easier for him to ignore your marketing.

Needless to say, that’s kind of the opposite of how the Cipher is supposed to work.

Your message needs to be novel in some way. If it isn’t, it not only gets lost in the racket, but it doesn’t even get heard in the first place. I think this is why many advertising and design people put so much emphasis on “originality” — because, despite being incompetent buffoons, they instinctively know that novelty is critical to being noticed. But of course, novelty without clear relevance to Sam just sends you skidding about helplessly on the slippery surface of irrelevant creative brilliance — as Ogilvy used to quip.

We’ve actually covered this already, way back in lesson #1. Reframing is just an example of using contrast. But now we’re going to be more intentional about understanding it as a principle unto itself.

Does it really matter?

Well, I don’t know what industry you’re in (it’s probably not commodities) — but I’d still like to quickly share some interesting stats I saw from Daniel Levis. I imagine these are somewhat approximate, and change constantly over both geography and time — but they still reflect a general trend in every market on earth:

Just 25 years ago there were...

4 running shoe styles to choose from — today there are 285.

17 over-the-counter pain relievers — today there are 141.

20 soft drink brands — today there are 87.

4 types of milk — today there are over 30.

13 choices on a McDonald’s menu — today there are 53.

12 major dental floss brands — today there are 68.

This kind of thing is happening in every industry, and it’s only getting worse as the internet lowers the barrier of entry into many marketplaces.

20 years ago it was really hard to start up and grow a business selling, let’s say, male enhancement drugs. If you needed help in that department you’d go to your doctor — because, well, no one wants to fly to the dodgiest parts of Mexico or Pakistan and risk getting shivved on the off-chance that the little blue pills they make in those sweat-shops are filled with more than sugar.

Today...well, you know.

Or, if you wanted to be a freelance writer 20 years ago, you had to earn it by not only being good at it, but having the tenacity to slog through hundreds of gatekeepers and editors — and then get lucky enough to find some who were willing to give you money without a tie-down contract.

The same kinds of obstacles existed in most industries — which today are sullied by internet scammers posing as skilled professionals, just because they can. (Excluding advertising, of course; that was filled with scammers since it became an industry 100 years ago.)

So what do you do if, for example, you’re a web designer and you actually don’t suck, because you’re not a college student living in your parents’ basement who has a talent for using online website builders, but no grasp of business objectives or direct-response principles? How can you make sure that Sam doesn’t read your website and quickly conclude that you’re basically the same as a kid with $40 to spare for web hosting and a domain name?

Well, it’s not a trick question — the obvious answer is, be brazen and just tell Sam about how most web designers suck, and why.

I know because I’ve used this exact message as a major lead-generation method, in the form of a report on why most web designers suck. I found that many marketing people, who don’t do web design themselves, but do have big audiences who need websites, were keen to share this with their lists. It’s pretty helpful information.

3 components of contrast

As with clarity and candor, I break contrast into three major elements.

1. Isolation

This is what you might call “basic contrast” or “contrast simpliciter.” Isolation just is contrast — it’s what contrast is when there isn’t really anything else going on. Something sticks out — that’s isolation.

This is very dependent on context, so it’s impossible to exhaustively list every way you might be able to create isolation — the list will look different for every market, for every product, for every business, even for every customer, because it depends on Sam’s existing expectations and knowledge. But let me give you some types of isolation that commonly crop up in writing copy:

Visual contrast: This might sound odd, since this is a program on copywriting rather than design — but how text looks on the page, how it blocks up or spreads out, how it chunks or sprawls, is very important for how inviting it is to read. I won’t go into detail on this here — we’ll cover it in a later lesson.

Unique selling propositions: As a general rule, this is a first-class example of isolation in the more abstract sense. A USP picks a benefit which is different, and therefore stands out to Sam simply because no one else has it (or says they have it). I actually think a USP, in the typical sense, is relatively useless to you as a freelancer unless you’re in a somewhat remarkable situation, but it is a classic kind of isolation.

Controversy. Sometimes this might fall under incongruity or intrigue (below) — but on the other hand, Sam can already know what you’re going to say; so neither of these is necessarily in view. Controversy isolates you in Sam’s mind very effectively: you stand out because you have the courage to say something that other people would be afraid to; and you stand out because you say something he strongly agrees (or disagrees) with. And of course, you stand out from those you disagree with.

I have used this very effectively in my own business — and continue to do so — by taking “internet marketing gurus” to task for basically being criminals. Doing this, I automatically isolate myself from them and seem more trustworthy by comparison (if I do it right). An opposite effect also occurs: they are isolated from me, and seem less desirable. This is very powerful...provided Sam has good reason to trust what I’m saying! (Which gets into the fourth C, connectivity — more on that another time.)

2. Incongruity

This covers a wide gamut of the ways contrast can be created. Reframes, which you’ve seen, are an obvious example — but incongruity goes a lot deeper than this. There are many ways of using it to both get and especially to keep attention.

For instance, incongruity is present within my “web designers suck” lead-gen method in several ways. Here’s the opt-in page I created for it:

You can also download the report itself to see how it works:

Some of the elements of incongruity in the above example are probably obvious:

The natural reaction people tend to have is, “Whoa, you aren’t supposed to rag on your competitors like that!” It’s an incongruous thing to do — unexpected.

The “how to actually choose a web designer” angle implies that the method people typically use is wrong. And I emphasize this by saying that my report may come as a bit of a shock — implying that Sam will learn is incongruous with what he currently believes. (Another way to think of incongruity is in terms of a kind of surprise factor.)

Along the same lines, when I say that the most important question to ask when choosing a designer has nothing to do with his process or aesthetic; and that most designers are actually artists and not designers at all — this is all emphasizing incongruity with what Sam currently thinks, or at least what the established wisdom is.

There’s also a lot of other incongruity a little further below the surface, which is doing a lot of hard work for me:

When I say that some designers are “considerably less equal than others,” that’s incongruous because it’s technically a contradiction in terms. In fact, there’s a double incongruity, because I’m referencing Orwell to say the opposite of what he originally intended by this phrase.

The overall tone of my copy is incongruous with what is considered “professional.” It’s also incongruous with the self-absorbed chatty style you often see on designers’ websites — a great example of which appears in my report itself, with the “Big Generic Welcome” used by 7 in 20 designers: “Hello! I’m a graphic designer who is passionate for creating modern & functional design that provokes feelings.”

In terms of the copy’s tone, humor is a big element, as it is in all my copy. Not that I consider myself a comedian by any means, but I do have a sense of humor — and a bit of an odd one at that — which I try to let show through in my writing. So for example, I just think “gibbon” is a funny word, especially when applied to people. Needless to say, humor requires candor, but it also trades on incongruity. That’s what makes stuff funny: “surprise factor.”

A lot of incongruity trades on humor or shattering expectations (which itself can be funny). To give you another example, MailChimp often uses this well (less now than they used to, though). They have their chimp mascot. He’s kind of cute and funny and definitely unexpected for a company offering serious email marketing services. Then they have little incongruities through their site — like their “MonkeyRewards,” which adds an affiliate link to the bottoms of your emails, but is described as, “Include MonkeyRewards badges in your campaigns to spread the monkey love!” Now, I don’t know if they’re still doing this, but Monkey love is not something you expect to hear about from an ESP. In an older version, the toggle options for “Use MonkeyRewards?” were “Yes” and “No (I’m a party pooper).” Same kind of deal.

This also illustrates that incongruity often comes in the form of personality. As we’ve already seen, on the web — sad but true — showing any sign of personality is rare, which is why candor is so important. The bland, indigestible copy churned out by marketing committees is not engaging. So personality is incongruous just by nature.

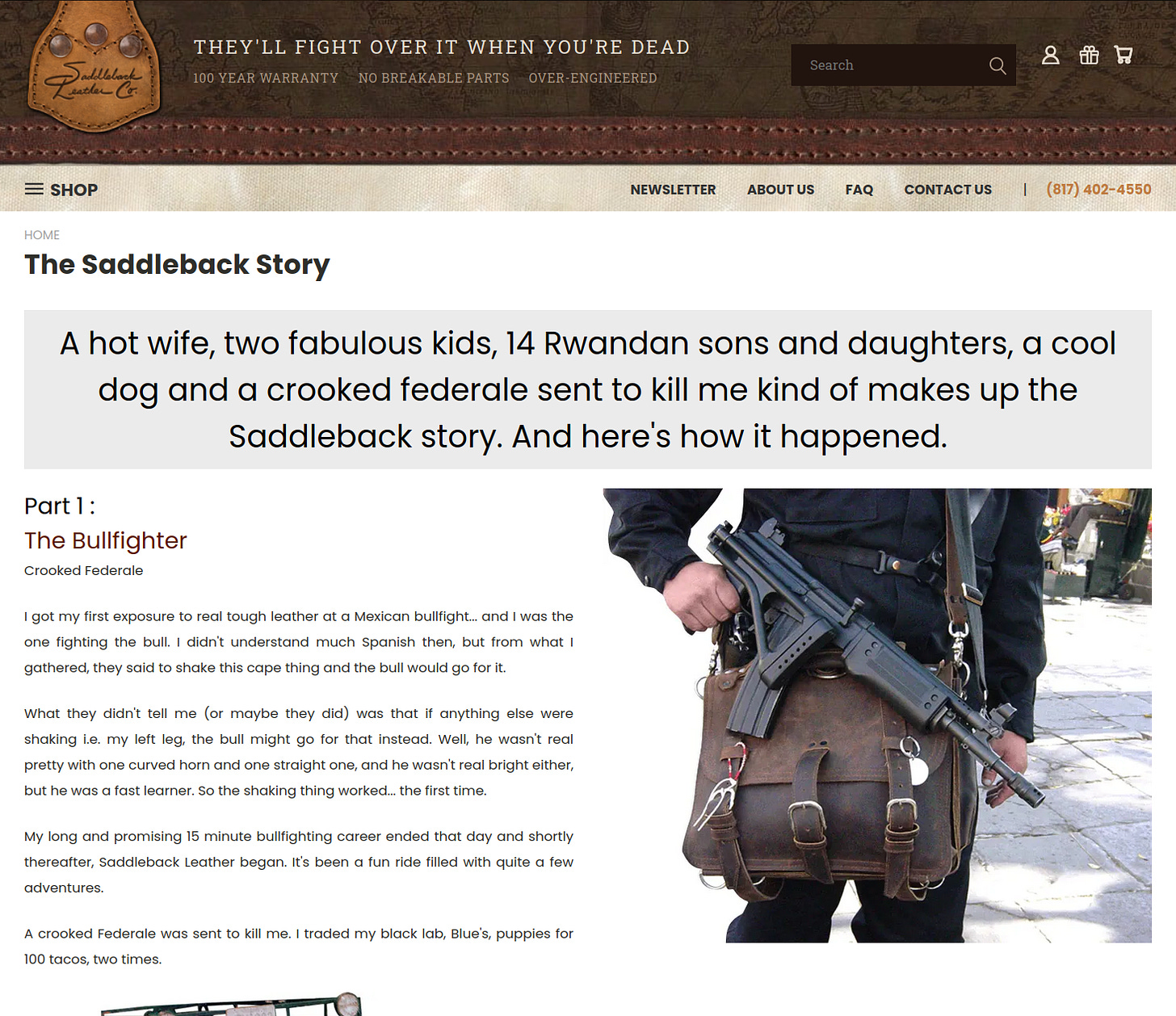

Another example comes from Saddleback Leather.

For example, their about page starts with an amusing story about a bullfight — incongruous both because bullfighting and leather have nothing obvious to do with each other, and also because the actual content of the story is funny (humor is always an implicit example of incongruity).

Similarly, their long-time homepage headline, now become their tagline, uses incongruity in the same way:

“They’ll fight over it when you’re dead.”

3. Intrigue

The final component of contrast is intrigue — anything that builds suspense or makes your reader curious.

This means, of course, that contrast is present in all great fascination bullets, and also in all great stories.

As with incongruity, intrigue comes in many forms, some overt, and some not so overt. As our first example, take the Saddleback Leather story just above. Here’s how it starts:

I got my first exposure to real tough leather at a Mexican bullfight...and I was the one fighting the bull.

What’s your first instinct after reading that sentence? Probably to read the next sentence, right? You want to know what happens to the author. Why is he fighting a bull? Does he get kicked or gored? How does the leather factor in?

Any good story automatically generates and maintains intrigue in the form of suspense and curiosity. This is why mystery novels are among the most popular genre of books — they not only have natural intrigue by merit of being stories, but the stories themselves are about intrigue! You see the same thing with a lot of movie and TV plots: as studios have started to hone in on money-making formulas, the “mystery box” format has preliferated.

Intrigue causes us to become emotionally invested in characters almost instantly. We need to know what happens to them. (Remember how in lesson #4 I mentioned that the essence of story is not plot, but character? Yeah...)

Notice also that the intrigue of the Saddleback story trades on incongruity — we would be much less invested and much less interested if the author started by talking about something mundane and “normal,” like driving to work or falling asleep. It is the oddness and surprise of the bullfight that stimulates our intrigue. And I use a similar technique in my email campaigns all the time, by telling odd stories about living on an orchard or riding a motorbike — things uncommon to the average reader’s experience. It’s not so much that there is anything serious at stake in these stories — that is not what makes them intriguing. It’s just that they’re unusual or quirky. They’re incongruous with your typical marketing advice emails, and even with how you expect a marketer’s personal life to look — so this makes them a bit intriguing.

Another way of using intrigue is by being a whistleblower. I use this quite often in various ways — some fairly mild, and some quite intense. I use it the “web designers suck” lead-gen report. And I use it in some of my emails — something we’ll look at when we start learning to write email campaigns later.

For instance, I wrote some popular and very strongly-worded emails a while back. Two examples:

“The vicious in-circle of internet marketing” — where I made comments like, “The internet marketing niche is an incestuous cesspit of lies, manipulation and bald incompetence. On the surface, there’s the appearance of highly-skilled experts being highly paid to provide high-value products to people like us.”

“Gurese”/English translations from my readers — with reader-submitted “translations” of guru catch-phrases, like:

I didn’t plan to do this, but I’m doing an extra webinar = I always planned to do this to try to get more sales.

We closed registration a week ago, but a few people haven’t taken up their slot, so there are now a very small number of places available = We didn’t sell enough so now I’m trying another scarcity play.

Our server crashed so we’re opening up the sales page for one more day = I’m a despicable liar only interested in getting as much money from you as possible.

Basically this kind of approach works because people love to see other people air the dirty laundry. Particularly if it’s something they suspected was going on but didn’t have proof for (so they get to say, “I knew it!” and feel all self-righteous and clever). It’s the same basic principle as gossip rags. Magazines like Women’s Day are actually well worth studying — not for the tripe inside, but for the headlines! (In case it’s not clear, I’m not advocating gossip; I’m just saying the same principle is at work.)

So story and “good gossip” are two extremely powerful ways of building intrigue to produce contrast. But there’s a third major method I use often. Looking back to my “web designers suck” opt-in page you can probably spot it. I do something very obvious on that page which I do on nearly every sales page I write: I introduce the topic and the product, so readers know what I’m talking about...and then I tease the living hell out of them with bullets that tell them all about the lessons they’ll learn, but not what those lessons are.

I do this all the time in email marketing campaigns as well. Ian Brodie used to messaged me each time I did, to complain about how maddening it is having these “fascinations” tickling away like splinters in his mind for the rest of the day. Here are a few examples he called out for driving him nuts with curiosity (these were selling a copy of my now-retired Attention-Thieves’ Communiqué):

How dodgy martial arts charlatans who want you to believe you can beat Batman with your pinky can teach you to increase your sales. Er, no, it’s NOT by studying their underhanded sales pages :)

The single most overlooked reason most targeted traffic doesn’t convert— and proof that simply being more persuasive will have utterly no effect on fixing it

3 simple — but not necessarily easy — elements any message must include, to convince a prospect to give you a chance

Why the essence of stories is not plot at all, what it actually is, and how you can take advantage of this little-understood fact to vastly improve the psychological effectiveness of your marketing material

These kinds of fascinations are what you will learn to write this week. For now, a simple exercise to start you off...

Homework

Nothing very strenuous today. Just a simple exercise that will give you some handy reference material for writing your fascinations later this week.

Brainstorm the key benefits Sam will get from your offering.

If you’re offering an information product, work through it and try to list as many of the lessons you reveal as possible. Make a note of where you can find each one (page numbers etc).

If you’re offering a consultation, think back to previous ones you’ve done (even better — listen to recordings if you have them), and list all the major insights your customers gained; as well as all the objectives you plan to achieve for Sam in each call, and the notable things you intend to teach him.

If you’re offering a physical product or an online service, you won’t be relying on curiosity — your method will be a little different. Intrigue will still be helpful, but so will isolation and even a little incongruity: list as many of the features and benefits of your offering that you can, especially focusing on those that differ from your competitors, or are unique to you. A helpful way of finding more, once you’ve covered the basics, is to ask what downsides there are to Sam going to some competitor or other instead.